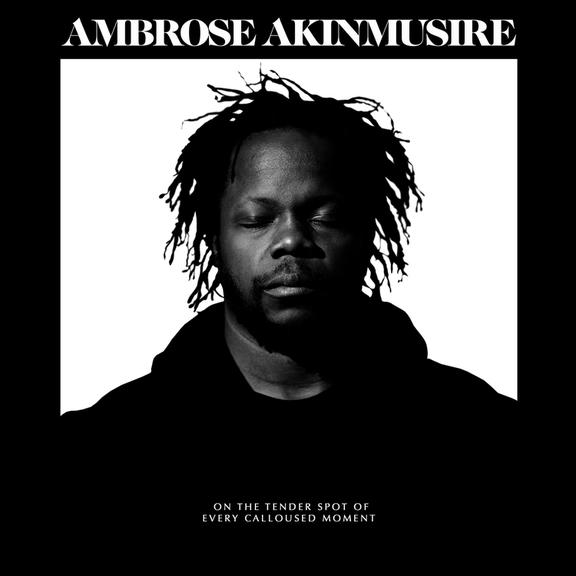

Ambrose Akinmusire’s Owl Song feat. Bill Frisell & Gregory Hutchinson (USA)

Ambrose Akinmusire: trumpet

Bill Frisell: guitar

Gregory Hutchinson: drums

Für dieses Konzert gibt es keine Erlaubnis für den Live-Stream. Wir bedauern...

There is no live stream permission for this concert. We regret...

Seit Jahren als Erneuerer des Jazz-Genres gefeiert, hat Ambrose Akinmusire die Veröffentlichung seines neuen Albums „Owl Song“ für den 15. Dezember angekündigt. Es ist das Debütalbum des US-amerikanischen Trompeters und Komponisten beim Label Nonesuch Records. Für die Aufnahmen tat sich Akinmusire mit seinem neuen All-Star-Ensemble aus Gitarrist Bill Frisell und Drummer Herlin Riley zusammen.

„Dies ist meine Reaktion darauf, von Informationen überrollt zu werden“, sagt Akinmusire über Owl Song. „Diese Platte verkörpert mein Bedürfnis, einen sicheren Raum zu schaffen. Das ist es, was ich zum jetzigen Zeitpunkt wollte. Ein Teil der Herausforderung war: Kann ich etwas kreieren, das sich an einem offenen Raum orientiert, so wie es einige der Platten tun, die ich am meisten liebe?“

Die Mitglieder dieses Trioprojekts bewegen sich normalerweise in unterschiedlichen Kreisen. Doch Akinmusire erschafft seine eigenen Klangkreise. Stets auf der Suche nach neuen Horizonten, kristallisiert sich nach und nach eine Vision heraus, die sich aus den unterschiedlichsten Quellen speist – herkömmlicher Jazz ebenso wie Avantgarde, klassische Kammermusik oder Hip-Hop.

Im Laufe der Jahre hat Akinmusire mit so unterschiedlichen Künstler:innen wie Rapper Kendrick Lamar (auf „To Pimp a Butterfly“) und Violinistin Helen Kim von der San Francisco Symphony zusammengearbeitet. Der Klang seiner Trompete ist „schwer zu greifen, selten mit einer klaren Auflösung, zugleich aber auch rubinrot und von großer Dringlichkeit“, umschreibt es die New York Times. „Wie kaum ein anderer Improvisator in der zeitgenössischen Musik hat Akinmusire eine Art des Komponierens erfunden, die sich komplett von den starren Konventionen des Jazz löst.“ (Warner Music)

My former trombonist the late Charles "Majeed" Greenlee played in some of the best bands in the late Forties and early Fifties, most notably Illinois Jacquet, Billy Eckstine, and Dizzy Gillespie. He had worked alongside many of the great soloists (was himself) during his career: Dexter Gordon, Yusef Lateef, Art Blakey, Sonny Stitt, J.J. Johnson et al. He and John Coltrane were "stablemates" (“roommates") during his stint with the Eckstine band.

Like many musicians of the previous generation, Greenlee possessed a wealth of anecdotes, like this one he recounted of Trane:

One night after the Eckstine band had concluded their performance, he and John retired to their room and, according to his wont, Trane would continue to practice as though the gig were a seminar leading to another class the following evening. It was a four-finger exercise for the left hand in the upper register that the trombonist regarded with keen interest but eventually nodded off to sleep. He awoke the following morning, glanced over at Trane's bed, and he was still working on that same figure for the left hand.

Greenlee added with a humble smile: “I was impressed.”

I offer this introduction as a certain counterpoint to an observation made to me by my wife's son, Martin, who first brought Ambrose to my attention.

In 2012, I had the idea to reprise the Attica Blues orchestra in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Attica prison uprising. I was in the in the midst of choosing the trumpet section when Martin asked me if I had heard of Ambrose Akinmusire. I had to admit that I had not. Subsequently, he played a recording for me which I found quite remarkable and I said to myself (quoting my ancient drummer Beaver Harris):

This is the Cat!

Indeed he is. I found his sound to be unique. His solos fresh, explosive. His legato slightly reminiscent of saxophone sub-tone, as one note melded seamlessly into the next.

Our rehearsals took place in southeastern France in a picturesque little village near Toulon. This was also the site where the first concert would be held. We practiced the music intensely, five hours a day for two weeks. One afternoon during lunchbreak we got into a discussion about Ambrose. Martin provided an anecdote which provoked the reference to Trane:

He observed that when Mr. Akinmusire was not needed in the orchestra, he would continue to work, strolling quietly into to the garden adjacent to the rehearsal hall and continuing to play his instrument. I immediately recalled John when he was performing with Monk at the Five Spot; how he would exit the bandstand taking a sharp left to the kitchen and continue to play throughout the intermission until the next set, never removing the horn from his mouth. I didn't anticipate that I would one day get to put these observations in print. I'm quite grateful to Ambrose for the opportunity.

Most importantly because the music opens new portals and announces the voice of an important young innovator.

I was particularly curious about a piece which Ambrose calls “Tide of Hyacinth,” which contains a very strong vocaI rendered in an African dialect. I was inspired enough to send him the following email:

You and the pianist have a close rapport. The compositions are quite original-quite interesting-intervals and scalar inventions. You feel the music, this is evident in the solos which make the written work dance.

Question: who is singing on “Tide of Hyacinth”? Very clever. It provides a traditional African dimension to contemporary African-American music (“jazz”). Sounds like an African language: Ashanti? Kru? Yoruba? Manding? Wolof? First time I heard the African voice used in the context of music inspired by the language of Armstrong and Bechet.

He replied that the vocalist sings in Yoruba, the language of the people of southwestern Nigeria and Benin. He added that his father (who is African) was originally designated to sing, but finally he chose Jesus Diaz, who is Cuban. Many Cubans are descended from the people of Nigeria, Benin (formerly Dahomey), and Congo which has resulted in the merger of African and European culture. For example, Catholic deities have corresponding Yoruba identities, a process known as syncretism. Catholic Saints are defined as Orixa or Loas. The Virgin Mary is celebrated as the Loa (Orisha) Yemaya Erzulie or Oshun . Thus, the Black Virgin.

Apart from the interesting titles he provided for the musical works, the compositions themselves are quite original. You will be captivated by the charismatic ambience and musical eloquence of the music of Ambrose Akinmusire.

This is the Cat!

—Archie Shepp, April 2020

https://www.ambroseakinmusire.com/