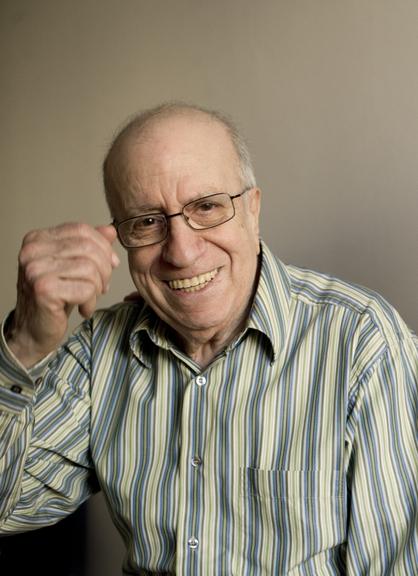

Martial Solal is quite simply a living legend. John Fordham visits the 82-year-old jazz pianist

Martial Solal lives in Chatou – the island-like Paris suburb on the Seine they call the ville des impressionistes. His house is so unlike any jazz musician's home I've visited that I feel I've flipped into a parallel world. Peering like a child through the high metal fence at a tree-shrouded villa beyond an ornamental garden, I'm in a fairytale in which jazz artists are feted, instead of consigned to dividing up the door money. But eventually I have to break the spell, press the buzzer, and wind my way through the shapely flowerbeds to meet France's most famous living jazz artist.

"Jean-Luc Godard has something to do with the story of this house," Solal says, with a boyish grin, worldly and self-deprecating at the same time, that despatches his 82 years in an instant. He's referring to the then 29-year-old Godard's fast, documentary-like 1960 drama A Bout de Souffle (Breathless), for which the Algiers-born pianist composed the score. That classic of the French new wave returns to the art house circuit from June, rereleased to celebrate its 50th anniversary, but its cult status has been earning Solal royalties for years. "I tell people it's like I won the Lotto," Solal laughs. "It was very fantastic luck for me, because back in 1959 when I did it, I was mainly known for being the house pianist in the St Germain des Prés jazz club. Fortunately, the film-maker Jean-Pierre Melville, a jazz fan who knew my work and was a close friend of Godard, suggested me for the job."

Solal is due to play in England twice this year – with classy bass and drums siblings François and Louis Moutin at the Bath International Music festival next week, and in a solo gig at the Wigmore Hall in November's London Jazz festival. "The most difficult thing for me now is to practise every day," Solal says, as we settle in his sunlit studio, with its hearthside sculpture of a luxuriously stretching cat, telescope, albums and sheet music, along with his grand piano. "Playing unaccompanied is the most challenging. Even if I don't play a concert for one month, or two months, I must practise so I know my fingers will follow my thoughts – otherwise it doesn't seem honest to me. If I can't do that, I'd rather stay home."

Though Solal's amateur opera-singing mother introduced him to the piano aged seven in the French colony of Algiers, and he learned jazz with a charismatic local bandleader as a teenager, he's largely self-taught – even down to immersing himself in classical composition and technique "to become a better player" in the 60s. That discipline has generated more than 20 film scores, a concerto for piano and orchestra that led to the founding of France's Orchestre National de Jazz, star status in New York in the 60s when hardly any European jazz artists performed there, an unprecedented 30-concert solo run on French radio in 1993-94, and receipt of Denmark's Jazzpar prize in 1999.

Solal achieved all that by picking up music as best he could – his only option as a teenager. After 1940, Nazi race laws in the colonies of occupied France excluded him from school as the son of a Jewish father, although he continued private music lessons. "My teacher in Algiers then was a neighbour of my aunt," he says. "A big, fat, impressive cat who played piano, saxophone, drums, accordion, clarinet, trumpet, everything. When I hear him play jazz, I get crazy. I become his pupil, then join his band for five years, playing piano and clarinet like Benny Goodman. It was just dance music, tangos, waltzes, only a little bit of jazz. And it was 1941 or 42, so we didn't know about Charlie Parker and modernism yet. But it was enough."

Solal moved to Paris in 1950 and met expat US drummer Kenny Clarke, a one-time Harlem cohort of Parker and Dizzy Gillespie in launching the bebop revolution. The two struck up a vivacious partnership in the house band at the St Germain des Prés club, a prestigious stopover for touring American jazz stars. In his first recording session, Solal found himself accompanying the Belgian Gypsy guitar legend Django Reinhardt, who turned out to be playing on his last gig. The pianist made an album of standards with saxophonist Sidney Bechet, a New Orleans contemporary of Louis Armstrong's with a blazing tone, who was almost canonised in his adopted France.

"I don't own that record I made with Django," Solal says. "I never wanted to hear it because I was sure I wasn't that good, and I was very nervous. With Sidney Bechet, it had been my idea. There was a war between the modernists and the traditionalists, but I thought maybe jazz could be one big family. People said he was a bad character, made trouble, but not that day. Of course, I loved doing it because it was part of the story of jazz. But I knew it wasn't going to be my direction."

Solal was anchoring the St Germain des Prés band (and beginning his speciality career as an unaccompanied soloist, inspired by piano virtuoso Art Tatum) when he got the call for Breathless.

"Godard had no ideas about the music, so fortunately I was completely free," Solal recalls. "He did once say, 'Why don't you just write it for one banjo player?' – I thought he was being funny, but you couldn't be sure with him. Anyway, I brought a big band and 30 violins. I never found out if he liked it, even now, but it seems to have worked. His films got more obscure later, but he was very interesting then, the films were very innovative but they still had a story.'

Breaking with traditions but always telling a story is Solal's guiding light. He's a brilliant improviser – last year he played a three-encore solo gig at London's Kings Place, in which Broadway songs flowed into Duke Ellington classics, Thelonious Monk themes, bebop anthems or originals, as if they had always belonged together. Solal says of his solo concerts: "I'm free to do anything that comes from my mind in the moment. If it's out of the context, it's OK, it's just the beginning of a new story."

Though he's inclined to joke about how lazy later years are making him, Solal clearly relishes the continuing worldwide demand for his work. Offers come from all over Europe and from the States, he presides over the international jazz piano competition in Paris that bears his name, and he continues to run his 10-piece New Decaband – a typically quirky brass-dominated outfit, in which he uses the remarkable vocal technique of his daughter Claudia to mimic sax-like textures.

But France's culture, traditionally jazz-friendly with its sympathetic arts establishment, is today closer to the UK's. "Jazz has both an important place in France and no place," says Solal. "Two thousand people might come for a concert, but on the big radio and TV stations, we don't exist. Maybe for 10% of the population this music's very important, the other 90% don't even know the biggest French, or American, or English names. But as long as we can live, and play the music we like, it's too bad for the 90%, it's their loss. Jazz is all about conversations, in duets sometimes even love stories. Playing solo is a conversation with myself, playing with others you have to listen, and respond. It's all still a very exciting game to me." (John Fordham, The Guardian, 2010)