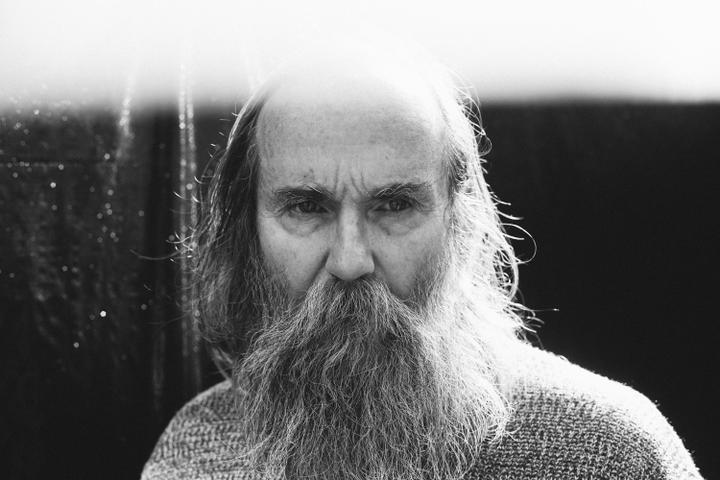

On December 7th Erased Tapes present ‘Fallen Trees’ – the new album by ‘continuous music’ pioneer and literal force of nature Lubomyr Melnyk – known as ‘the prophet of the piano’ due to his lifelong devotion to his instrument.

The album release coincides with Melnyk’s 70th birthday, but despite the autumnal hint in its title, there’s little suggestion of him slowing down. Having received critical acclaim and co-headlining the prestigious Royal Festival Hall as part of the Erased Tapes 10th anniversary celebrations, after many years his audience is now both global and growing. The composer is finally gaining a momentum in his career that matches the vibrant, highly active energy of his playing.

Cascades of notes, canyons and rivers of sound: there’s something about his music that channels the natural world at its most awe-inspiring. In ‘Fallen Trees’ the connection with the environment continues, taking its cue from a long rail journey Melnyk made through Europe. Glancing out of the window as the train passed through a dark forest, he was struck by the sight of trees that had recently been felled. “They were glorious,” he says. “Even though they’d been killed, they weren’t dead. There was something sorrowful there, but also hopeful.” That sense of sadness touched by optimism infuses the album, too: rarely has Melnyk made music so shot through with melancholy and regret, but which sounds so rapt, even radiant.

Drawing comparisons with Steve Reich and the post-rock group Godspeed You, Black Emperor!, Pitchfork praised his 2015 album ‘Rivers And Streams’ for it’s “sustained concentration and ecstatic energy”. That energy is present in ‘Fallen Trees’ too, but at points the tone is quieter, the mood darker and more wistful. At points elsewhere on the album, despite being rooted in the wonders of the natural world, there’s a kaleidoscopic quality in the fractal flurry of notes and the broad spectrum of colour they summon.

The work that gives it its name, the five-part, 20-minute ‘Fallen Trees’, is one of the most ambitious and demanding pieces he has ever created. Though the music is – as ever – Melnyk’s own, ‘Fallen Trees’ once again features a number of Erased Tapes artists. Japanese vocal artist Hatis Noit, whose first EP ‘Illogical Dance’ came out to much acclaim earlier this year, lends ethereal vocals, floating mysteriously above the surface of Melnyk’s eddying piano lines before diving far beneath. Other contributors include Berlin-based cellist Anne Müller, a sometime collaborator with Nils Frahm, and American singer David Allred, the most recent addition to the label family. “More than any of the albums that I’ve done, it’s a real collaboration,” Melnyk insists, emphasising how much he owes to his producer, Erased Tapes founder Robert Raths.

Born in the Ukraine in 1948, Melnyk fell for the piano at an early age. Given lessons as a young child after his family emigrated to Canada after the iron curtain came down, he was immediately transfixed by the possibilities of the instrument. “On the piano, you can create whole worlds,” he reflects. “I realised that it could be an orchestra, a choir of sound.”

After studying classical piano and graduating with a degree in Latin and Philosophy from St Paul’s College in Winnipeg, in the early 1970s Melnyk found himself in Paris. Homeless and in desperate need of money, he supported himself by accompanying dance lessons for a company run by the experimental choreographer Carolyn Carlson. The experience became a kind of epiphany: watching Carlson’s dancers, he began to play a new kind of music, spontaneous and improvisatory – responding not to rigid classical conventions but the dance he saw unfolding. Using the sustain pedal to create echo and reverb, he transformed free-flowing cascades of notes into hypnotic waves of sound. Eventually he found a name for this new style: ‘continuous music’, which he uses to this day.

Critics have detected the influence of Ravi Shankar and other Indian styles in Melnyk’s music, along with the insistent, repetitive textures of minimalist pioneers such as Steve Reich and Philip Glass. Melnyk himself cites his debt to the American composer Terry Riley, particularly the legendary 1964 work ‘In C’, which he says “opened the world for me”. But he adds that if you listen carefully, you’ll also be able to hear the lilting contours of traditional Ukrainian folk music.

It might be truer to say that there is genuinely nothing quite like Melnyk’s work: a unique musical pioneer, he has defiantly carved his own path. “I don’t say to people I’m a composer,” he declares. “I don’t know what I am.”

Melnyk composes, as he plays, at the piano, feeling out lines and individual rhythmic cells that bubble, undulate and gradually expand into vast, interlinked frameworks. Asked to describe what it’s like to live inside his music, he says “my whole body is transformed as I play, it honestly feels like that. My fingers feel like the winds of the world; it feels like you’re physically transcending dimensions.”