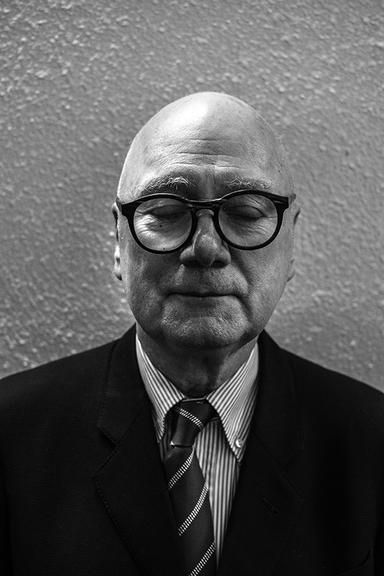

Franz Koglmann 'Near Blue' (A)

Franz Koglmann: trumpet, fluegelhorn, compositions

Gert Schubert: violin

Kurt Franz Schmid: clarinets

Sandro Miori: tenor, soprano saxophone, flute, alto flute

Rudolf Ruschel: trombone

Raoul Herget: tuba

Robert Michael Weiss: piano

CD Präsentation 'Near Blue' HAT HUT ezz-thetics 1056

We start the live stream approx. 1/2 hour before the concert begins (real time, no longer available after the end of the concert). By clicking on "Go to livestream" a window will open where you can watch the concert free of charge and without any registration. However, we kindly ask you to support this project via "Pay as you wish". Thank you & welcome to the real & virtual club!

The title is inspired by the Irish artist (painter) Sean Scully, whose works often (not only) revolve around the color blue, and of course "blue" is an important reference as a "blue note" in the world of jazz.

The program will also include some pieces that have to do with - or are inspired by - contemporary Austrian literature - e.g. 3 pieces named after Julian Schutting, or Franz Schuh, a piece that has already been performed twice at Schuh symposia, once with Falter editor Armin Thurnher at the piano. The lyricist Paul Celan is represented in this program with a setting of his early poem "Nachts".

There will also be pieces that refer to important protagonists of modern jazz, above all the trumpeters Miles Davis and Chet Baker.

Last but not least, some pieces will refer to the Viennese ambience, or Viennese atmosphere, such as "April In Vienna". (Franz Koglmann)

When the past and the present – and implicitly the future – comingle in jazz, the listener can become briefly unstuck in time; but unlike Billy Pilgrim in Slaughterhouse Five, who ricochets between the hellscape of firebombed Dresden, the banalities of post-war suburbia, and a pleasure dome in outer space. Rather, it is a glide through associations accrued over years and decades and the particulars of each moment an entry is added to the compendium. A necessarily labyrinthine route that repeatedly crosses itself, it is a historicizing journey, although its resulting history is not, as attributed to Arnold Toynbee, “one damn thing after another,” but a whirl of ideas posited decades ago, continually honed, and projected into the future.

Thirty years ago, Art Lange noted that Franz Koglmann understood Duke Ellington as a vortex of diverse sources inspiring a wide variety of works. Time has proven Koglmann to also be such a vortex. For more than a half century, he has taken the crisscrossing path, guided by an unlikely, sprawling constellation of composers and improvisers and writers and visual artists: Ellington and Vladimir Nabokov; Ezra Pound and Chet Baker; Bob Zieff and Rene Magritte; Jean Cocteau and Bill Dixon; George Russell and Yves Klein; and on and on, ever expanding. It is a list that reflects Koglmann’s provocative aesthetic, a critique of the standard Americentric jazz narrative that nevertheless honors – and savors – many of its greatest exponents.

The commentariat’s consensus that Koglmann’s is the aesthetic of cool is close enough for general discussion, even as it glosses over his off-center classicism and impeccably mannered subversions, as well as his extension of thornier Third Stream practices. Viennese cool is closer to the mark, as Koglmann triangulates aspects of Wiener Moderne – the formalism of Arnold Schoenberg and Adolf Loos; the exploration of sexuality by Gustav Klimt and Arthur Schnitzler; Hermann Bahr’s “romanticism of the nerves” – with jazz virtues. Koglmann applies the probity associated with Wiener Moderne to both his original works and his interpretations of jazz literature spanning “Ezz-thetics” to “At the Jazz Band Ball” to create music that is far afield from stereotypical cool jazz.

The Viennese component of Koglmann’s aesthetic reasserts itself on Near Blue – A Taste of Melancholy, beginning with its title. In an essay comparing mourning and melancholia, Sigmund Freud theorized the latter was the grief for a loss that eludes identification or comprehension, taking place largely in the subconscious. “A taste” suggests melancholy can be experienced like an amuse bouche, something best appreciated by the connoisseur; and “near blue” implies a critical distance, not a full immersion. While this Viennese-tinged dynamic between analysis and sensuality are prominent in album-length works like Venus in Transit, Let’s Make Love: An Imaginary Play in 12 Scenes, and Lo-lee-ta: Music on Nabokov, it presents differently on this collection.

Near Blue – A Taste of Melancholy is a snapshot of Koglmann unstuck in time, gliding between revamped, decades-old works and first recordings of more recent compositions. Four compositions included on prior recordings have been rescored for trio, quartet, and sextet. In each case, Koglmann transforms the material. Originally a lithe duet with Burkhard Stangl on A White Line, “April in Vienna” becomes a shadow-dappled cityscape in this sextet version; a space-privileging duet with Misha Mengelberg on L’Heure Bleu, the addition of trombone and tuba on “Nachts” pointedly evokes a long, uncertain night.

On “Franz Schuh” and “A Day’s Work,” Koglmann takes the additional step of restructuring the compositions, bookending the thematic materials with improvisations to give each a distinctly new shape. The latter also benefits from a simple shift in palette, substituting alto flute and piano for the original’s guitar and bass. Koglmann’s nod to the Viennese cultural critic entailed the overhaul of “Späte Liebe,” a setting of four Schuh poems for soprano voice and chamber orchestra included on Don’t Play, Just Be. In this trio for soprano saxophone, flugelhorn and piano, Koglmann distills the materials to piquant essences.

Koglmann also continues long-standing compositional practices in works toasting Baker and Zieff. Inspired by a photo of Baker wearing CAT brand shoes in a photograph that ran in a 1965 issue of the French Jazz Magazine, Koglmann used phrases from Baker improvisations as the basis for “Chet’s CAT’s Heels.” Zieff’s compositions, which Koglmann considers to be pinnacles of extended modern jazz, are echoed on “Waltz for Bob;” not only is Vienna a subtext of the piece because of its meter, but also because Zieff’s compositions were recorded by Art Farmer, who resided in Vienna for the last 30 years of his life.

The album ends with a three-part work relating to the work of Julian Schutting. The opening section uses a 12-tone row and its reversals that Koglmann composed for a performance with the Austrian poet, novelist, and essayist, during which Schutting recited a text about his friendship with the serial composer J. M. Hauer, who had dedicated a “Zwölfonspiel” to Schutting. Koglmann had originally intended to use Hauer’s tone row for the piece; unable to locate it, Koglmann devised his own. The piece encapsulates the album, as it seesaws between the ponderous and the puckish.

Although Koglmann uses serial techniques and has found inspiration in composers like Franz Joseph Haydn and Johann Strauss the Younger, he remains a jazz composer in the tradition of Ellington on essential counts: decades-long relationships with key players; incisive blending of instrumental colors; and unerringly pairing of soloists and materials. Koglmann’s septet mixes old and new colleagues. Rudolf Ruschel and Raoul Herget have been integral to Koglmann’s music for forty years; Robert Michael Weiss has contributed to various Koglmann projects for almost as long; and Gert Rainer Schubert first recorded with Koglmann twenty years ago.

The newcomers are Kurt Franz Schmid and Sandro Miori, who supply the warm highlights essential to creating the contrasts with lower-pitched brass that drive Koglmann’s charts. They also ably step into the void left by the passing of Tony Coe, delivering concise, engaging solos. Koglmann’s deft hand in distributing well-suited solo space to his colleagues is frequently confirmed throughout the album. Given his emphasis on composition and orchestration, Koglmann’s own solos are reminders that he is also an impressive improviser. This septet is a worthy successor to Koglmann’s Pipetets and Monoblue units; and like Ellington’s small groups, it provides insight into the chemistry of Koglmann’s art.

Near Blue – A Taste of Melancholy is a soundtrack for being unstuck in time, if just for an hour. It is a glide through a rich past and present, with glimpses of a future worth reaching. (Bill Shoemaker, December 31, 2023)